How can you sing a song if you have no voice? Disabled musicians, activism, technology, and the authenticity of creativity – Leon Clowes (University of Huddersfield, UK)

How can you sing a song if you have no voice? For many disabled people, prior to the advancements in technology in the 1980s, music making was limited at best and impossible for many. Consequently, the convergence of activism with the music technology revolution over the past thirty years has played a fundamental role in the creative development of disabled musicians. One of the key arts organisations working in this field is Drake Music, a national organisation that specialises in music making with disabled people using technology. As a non-disabled former musician-turned-charity-administrator, my fundraising career began by first working at Drake Music in the mid-1990s. I later returned as a freelancer in the early 2000s, and earlier this year I began working again at Drake Music.

Having returned for the third time over a twenty-year period, the changes in society and technology have had an enormous impact on the work that we do. For this article, the basis for reflection is a two-page manifesto ‘Music gives disability a byte’, published in the January 1987 issue of the New Scientist and written by the charity’s founder Adèle Drake with Jim Grant. The words of Adèle Drake, and sound artist Duncan Chapman are also included, emerging from our conversations in December 2015. Through this piece I hope to raise questions central to key notions of voice, authenticity, the musician, and musical creation in relation to the use of technology by disabled musicians. Each will be provided in bold, in an attempt to ‘Get Loud’.

Start Me Up

Technology affords the opportunity for creative expression for a disabled musician. But, as Chapman reflects:

There are issues of authenticity … and how is it authentically somebody’s voice? … It’s really apparent when you’re working with someone for whom communication is difficult – if it takes somebody five minutes to get every word out – then actually communication takes a long time – then how do I know it’s an authentic voice? It’s very easy with technology to set up your computer so when you push a button all the music plays. So how do I know it’s me? And what’s that got to do with me anyway?

If a song can be about anything, disabled musicians using the palette of technology are extending different forms and expressions of creativity that were not previously possible. The ‘voice’ of a non-verbal musician can instead be via music, noise, and sound.

Many thanks to the New Scientist for granting permission to use images from ‘Music gives disability a byte’, an article by Adèle Drake and Jim Grant. The images were taken by Pete Addis, the magazine’s staff photographer at the time.

Pragmatic research has considered specifically designed music programmes, and comprehensive guidance exists for music therapists applying technology in their practice. This laudable work advances knowledge of practical interventions, but what are disabled musicians creating with these tools and why is this important for others to hear and understand?

Those members of society with less social power, those on the margins of society, have fewer opportunities to present their chosen identities and are more susceptible to the identities ascribed to them by others.

Watts and Ridley (2006, p. 101)

Ripat and Woodgate (2011) note an absence of knowledge on the intersection of the cultural identities of individuals who use assistive technologies, and so make a call for further research. Additionally, there is a paucity of information on the if and how technology has authentically transformed the creative voices of non-verbal disabled artists through sound and music over the last thirty years. Within this piece, I hope to raise important questions on the nature of creativity which are easily overlooked by many of us who take our own capacity to create for granted. In asking ‘what would your social and cultural experience be like if you found yourself with barriers to “being creative”?’, I offer examples from a small group of individuals who have responded to this problem using activism and technology.

Sound and Vision: Communication of Creativity

If children cannot communicate, then no one can understand what they think.

Drake and Grant (1987, p. 37)

In much of the dominant academic discourse around music and creativity, the emphasis falls on competency and training, be that in a practical sense (as described by Gardner 1993) or a socio-cultural one (Hesmondhalgh 2013; Negus and Pickering 2002). However, the important point here, as highlighted in the quote by Drake and Grant above, is that heavily implied in this dominant discourse is the often-unspoken fact that when an individual is excluded from ways of thinking and talking about creativity, very often they are also excluded from creativity itself.

Thus, while every normal individual is exposed to natural language primarily through listening to others speak, humans can encounter music through many channels.

Gardner (1993, p. 119)

This resonates with my own observations of a music workshop in a South London residential home in the mid-1990s where the Drake Music workshop leader invited the adult participants to bring in recordings of their favourite music. From this group session, it was clear that the workshop participants, who had been living in residential settings for most or all of their lives had only been exposed to a limited number of audio-cassettes from within their own microcosms. This was a stark contrast from my educational, social, and cultural experiences, in which listening to the radio, watching television, reading music weeklies, having piano lessons, studying music at university, and frequenting record shops were interconnected components of my own musical experience and education.

While my personal cultural journey was mostly of my own volition, the major difference was that I had the choice to take this route. It would have taken any one of the workshop participants an enormous amount of self-determination to have anything like the exposure I had to popular music and cultural life in my teens and mid-twenties. The participants were keen attenders who clearly enjoyed the weekly Drake Music workshops, but it was clear to me that they had also experienced what was, to me, a poverty of cultural enrichment.

In the 2006 evaluation of the practice of Drake Music, Watts and Ridley claim that:

we learn to construct our own identities and shape our own images of ourselves. The music that we listen to and make play a significant role in these processes.(p. 101)

Therefore, our taste and knowledge of music can be central in defining who we are, who we want to be and how we wish to define our place in the world. For the people living in the residential home workshop I describe, the outlets the individuals had been limited and their choices restricted by their circumstances.

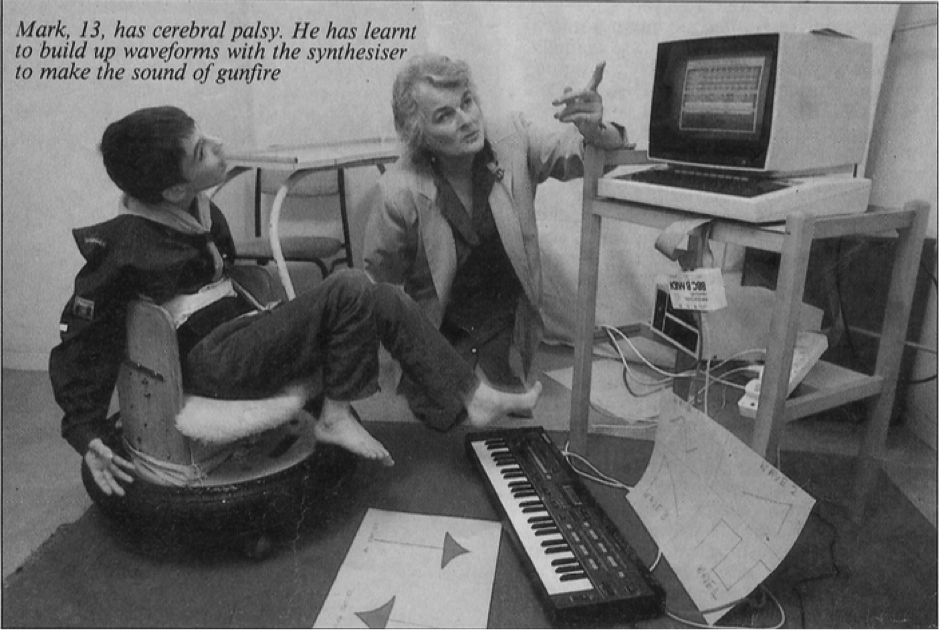

For some disabled people, communication itself is vital to day-to-day survival. Adèle reflected on how many disabled people have their privacy constantly invaded by others to achieve the functional necessities of feeding, bathing and toileting. She said that ‘you end up having intimate conversations that you would never normally have.’ Exploring this through sound, with one non-verbal pupil of Drake Music, the first sounds he created via a synthesizer were evocative of gunfire and a motor bike accelerating. As Adèle explained, the young man wanted to ‘make an impact’.

I would also assert that this was the young man experiencing having a voice for the first time. Technology allowed him to be loud, and he wanted to shout with his first words.

Talking ‘Bout (M)iGeneration: Accessibility as Activism

Action affects the world.

Drake and Grant (1987, p. 39)

Even as recently as the 1980s, many disabled people had to lead institutionalized lives, or, if they lived independently with their families, my own experience was that there were limited life choices open to them. My birth-mother Sandra’s physical condition deteriorated because of multiple sclerosis (MS). Sandra barely left the house except for a few family occasions. Adèle Drake’s twin sister was also diagnosed with MS at fourty, perhaps one motivator for us both becoming involved in this cultural world.

Although the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities only came into force in 2006, activists and Disability Studies academics have challenged the language used to refer to disabled people and the contextualisation of the issues that they face daily. By replacing the ‘medical’ model of disability (focussing on a specific disability or the disabilities of individuals) with the ‘social’ model (how society presents barriers for individuals), an attitudinal shift takes place. It is society that causes disabling barriers.

Activists such as Disabled People Against the Cuts have taken to the streets to protest, speak out and be visible; most notably in the face of recent government cuts, as scrutinized by Jamie Kelsey-Fry in an online New Internationalist magazine article in 2011. It could be argued that, in an artistic sense, the very act of being a disabled musician is a form of activism. The disabled musician has both the challenge and opportunity of pre-conceived or no expectations from audiences who have had no prior exposure to disabled creatives (Watts and Ridley, 2006, p. 102).

The arts sector infrastructure and practice of community and disability arts evolved in the UK during the latter part of the twentieth century. Prior to the likes of Drake Music, Graeae Theatre Company, Heart n Soul, Candoco Dance Company, Share Music, and The Orpheus Centre emerging in the 1980s and 1990s, arts organisations for whom the specific delivery of arts practice for, by and with disabled people (the catch-all moniker becoming ‘disability arts’) was a relatively new concept.

Up until this point, music provision was almost exclusively ‘for’ rather than ‘led by’ disabled people. The role of music was to heal or sooth: either the clinical intervention of music therapy, or the less formalised adoption of music in care settings. Music as therapy.

There always has been a huge continuum between what is therapy and what is education. And it goes on, all the time. So, of course, if you play music, it’s both therapeutic and educational in the sense that you learn to distinguish things if you’re listening.

Adèle Drake

As Adèle muses, there is overlap between music therapy and music education, but is this as true for us all as it is for a disabled musician?

I get quite political. Are we trying to ‘normalise’ people by making ‘normal’ music? I prefer the edges. Now we have sound art, this has made things more mainstream. Duncan Chapman

Duncan Chapman demonstrates his philosophy through his practice. He presented music created by children with severe, profound and multiple learning disabilities at Wigmore Hall in 2011 as part of a collection of pieces presented by numerous mainstream schools. As a deliberate act, Chapman ensured that the disabled children were the only class delivering their music via live electronics. Their sound was blisteringly loud against all the other school groups who played acoustic instruments. Chapman’s rationale was that, ‘the kids on the bus from the special school … you don’t meet them in normal life so they were the loudest.’ Chapman’s idea was to explore ‘hidden worlds’ and to ‘make the invisible visible’, presenting the mainstream audience with a world they might not otherwise see. These children are not to be pitied, they are shouting. The collision of loud noise and sound is a call to action, forcing the audience to open their eyes, possibly for the first time.

Chapman’s intentional use of electronic sounds transform the disabled schoolchildren’s musical voices into disruptive shouting. In considering this, I was struck by the parallels with the words displayed in a framed picture that hangs in the Drake Music office. They are taken from a 2009 poem ‘Get Loud’ by US poet Ruth Harrigan, who draws on her observations of a young boy who is a wheelchair user. These words crystallize the fundamental need for human expression, balanced with the frustration of the struggle of continually remaining unheard or misunderstood:

Get loud

or whisper.

Your voice

Your choice

Shout

One word

Or whisper

Words

Others strain to hear

Let them lean down

Toward your wheelchair

Their head touching yours

Their breath on your cheek

Asking

What did you say?

Then

Get loud!

The concept of communication and expression is challenged and questioned through art. In ‘The Non-Normative Speaking Clock’, sound artist Gemma Nash applies her lived experience to examine the implicit dominance of social construction about the way we communicate with one another. She draws a parallel to debates about body fascism; and through this piece, she is highlighting the politics of normativity in speech and communication. In collaboration with technologist Lewis Sykes, Nash reframes the iconic speaking clock’s precision and function by positioning her voice within its familiar context.

If disabled people’s activism is ‘Getting Loud’ to ensure that hidden voices are heard, how are digital technologies helping to amplify previously hidden voices?

The Times They Are A-Changin’: Technology as Transformative

MIDI and computers have provided professional musicians with the freedom that word processors brought to writers.

Drake and Grant (1987, p. 37)

In parallel to the societal shifts influenced by disabled activism, technological advancement has been the actor to facilitate the cultural evolution. Technology has engineered a shift in the possibilities for all creatives, but it has brought about nothing less than a revolution for disabled musicians. In the New Scientist article, one of the predictions made was that the ability to save and edit music would offer disabled musicians hitherto unprecedented opportunities in creative participation. Conversely, the disadvantages are that the process of music making would, in some ways, become too easy, or offer a bewildering amount of choices.

After completing her postgraduate diploma at the Institute of Education, the then school teacher Adèle Drake went on to establish Drake Music Project (named in memory of two of her daughters) with the mission to provide disabled children and adults with opportunities to make and learn about music via computers and technology. Drake pinpoints the adoption of switches in assistive technology as a significant milestone:

With my sister becoming ill, I knew she could draw the curtains or open the door with an electronic door, and that people could control an electric switch so a light would go around a computer screen with holes for ‘I want a cup of tea’. The technology was there but not yet on a computer screen.

Adèle Drake

During the mid-1980s, the research unit at Charlton Park School in Greenwich focussed on the potential applications of computers and switches for disabled learners. Word processors offered writers the facility to save data, and more crucially, to edit. Inspired by this technological innovation, Adèle began to run music lessons at the school using a donated BBC computer and Yamaha keyboard. In the world of hand-held devices with instant music apps, this kind of practice sounds quirky and quaint today, but it was both experimental and innovative for the time.

The GarageBand app is explicitly named by Chapman as a good contemporary example of swiftly offering impressive music making results in a classroom, and the touch and ease of use of an iPad is accessible for many in both mainstream and special educational needs settings. GarageBand utilizes predetermined sounds, and allows the user to record audio and to import external sounds and samples, and so the creation of generic music is straightforward. The iPad itself is a good example of technology built for other purposes but disabled composer and conductor James Rose and musician and workshop leader Ben Sellers set out to go beyond this, and reposition iPads in the minds of educators as expressive and creative musical instruments.

However, the relative ease of use of GarageBand does have the potential to discourage the learner from exploration of unfamiliar sounds and structures, and from the discipline of practicing and learning technique of an instrument. Chapman proposes that instead, technology should extend the potentials of music and sound art:

One has to work harder in a way … to find a way of making the sound itself … Why would I want to make my computer sound like a piano when I can use a piano? … I think people over-egg the amount of change … The basic acts of listening, perceiving and connecting are still the same.

Duncan Chapman

In contrast to the immediacy of GarageBand is Dr Tim Anderson’s E-Scape. While developing the embryonic computer music programme at York University, Dr Anderson became involved in Drake Music in the early 1990s, and his academic project developed into a switch-operated programme aiming to suit the needs of disabled composers so they can create without the aid of others.

E-Scape is a compositional and performance music system designed to suit the requirements of the broadest range of disabled musicians who use switches and eye gaze technologies, but the user journey is initially complex and does not provide immediate rewards. The programme’s development presents an endless pattern of complexities for iterations. On the one hand, with the programme being designed around an individual’s needs and requests, this programme is centred on the person learning to play and compose with the programme. However, because E-Scape is created to level the musical playing field for people who can only use switches, no-one will ever have a ‘quick win’ using the programme in the same way as is possible with GarageBand. A great deal of time must first be spent on familiarization of the programme by the user. However, the advantage here is that E-Scape is a programme that conceptually presents infinite iterations, potentially bespoke to any disabled musician.

Technological advancements have made sound production free to everyone. As disabled musician Lyn Levett explained in an email to me, ‘software has taken over from hardware’. The portability this offers means she is now able to compose at any time and in most places, rather than in a specific location at a prearranged time when the necessary technology and a facilitator is available to operate it. There are many positives to the creative possibilities that this portability allows for people with disabilities.

However, one downside to the democracy of sound production is the potential of the musician having too much choice. Chapman spoke of how the cost of studio hire in the 1980s ensured a limited number of takes, and, to a certain extent, the avoidance of over-production. This is important in the context of the disabled musician’s voice because all creatives using technology face an endless choice of sound possibilities, whereas the use of limited resources may better encourage discipline within practice.

The activism of co-creation is the route to what Chapman describes as ‘giving people a voice’ and with technology as a facilitator, the opportunities are open to ‘create music with the sounds that really belong’ to individuals and communities. Technology – both generalist and specialist – far exceeds Drake and Grant’s 1987 prediction of the removal of barriers to music making. It has become the musical voice and expression for many disabled and non-disabled musicians.

What will the future hold thirty years from today?

When I asked my interviewees this question, the responses varied greatly. Adèle Drake’s longstanding dream is a virtual online orchestra so that a real-time ensemble could include players from Australia to Argentina. Duncan Chapman enthuses about the recycling or upcycling of technologies, and the potential of new sound palettes that this presents. What strikes me is that the variance and landscape of music makers today involves technologists, coders, sound artists. The concept of what constitutes creativity in music has been stretched and expanded alongside technological advancement and societal shifts brought about by activism. This can only be set to continue. Therefore, the palette for a disabled musician’s creative communication is increasingly rich and nuanced.

At Drake Music today, a central ambition is that all music technology should be made fully accessible as a matter of course, rather than be an add on, or an extension of, existing technologies. The charity observes the social model of disability rather than the medical one, and so Drake Music’s Research & Development programme brings disabled musicians together with technologists and makers to create bespoke instruments. Our overarching artistic programme seeks to ask what is music, and how do we define what makes a musician? There is a real opportunity here; disabled musicians may be faced with low or no expectations from music consumers, but equally, they can be unfettered with these preconceptions. They have a blank canvas and this rich technicolour palette. There are no rules, and little need to create any new ones. As instruments can now be tailored to each individual, potentially, we can all have a unique musical voice.

By bringing together activism and technology with creativity, the disabled musician can now be centre stage. It was not a singular actor that made tomorrow’s world possible today, but rather a convergence of politics, resources, and co-creation through which cumulative change was possible and happened. Given the rate of technological advancement, the world of possibilities for the disabled and non-disabled musician may well be even further removed what we could possibly conceive today. And we can hope that the questions asked and the answers given will too be different.

To all the disabled musicians and activists, I say: ‘Get Loud’, Stay Loud, Be Heard.

References

Drake, A. and Grant, J. (1987) Music gives disability a byte. New Scientist, pp. 37-38.

Gardner, H. (1993) Frames of Mind: The Theory of Multiple Intelligences. London: Fontana Press.

Hesmondhalgh, D. (2013) Why Music Matters. Oxford: Wiley Blackwell.

Negus, K. and Pickering, M. (2002) ‘Creativity and musical experience’, in D. Hesmondhalgh and K. Negus (eds), Popular Music Studies, pp. 65-83, London: Arnold.

Ripat, J. and Woodgate, R. (2011) The intersection of culture, disability and assistive technology. Disability and Rehabilitation: Assistive Technology, 6:2, pp. 87-96.

Watts, M. and Ridley, B. (2006) Never Mind the Bollocks Here’s the Drake Music Project: A Capability Perspective of Dis/ability and Musical Identities. Taboo, Fall-Winter, pp. 99-107.

Leon Clowes completed his MA in Music (Popular Music Research) at Goldsmiths in 2016. Currently a part-time student at University of Huddersfield, his PhD focus is ‘Burt Bacharach’s (Un)easy Listening: A Model for Musicians from the Middlebrow of Popular Music’. This Riffs article is Leon’s first published piece of academic writing, and in 2018 he has two two book chapters due for publication.

Leon is the Development Manager for arts charity Drake Music, and he has worked and volunteered in the arts, health and social welfare sectors as a fundraiser and project manager, most notably for the Royal Exchange Theatre in Manchester and London Film School. Leon is also a Winston Churchill Fellow, having completed a very personal piece of research into families like his own that are affected by kinship care across eight states in the United States in 2012.

Leon Clowes